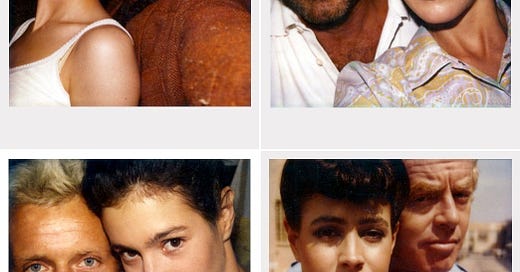

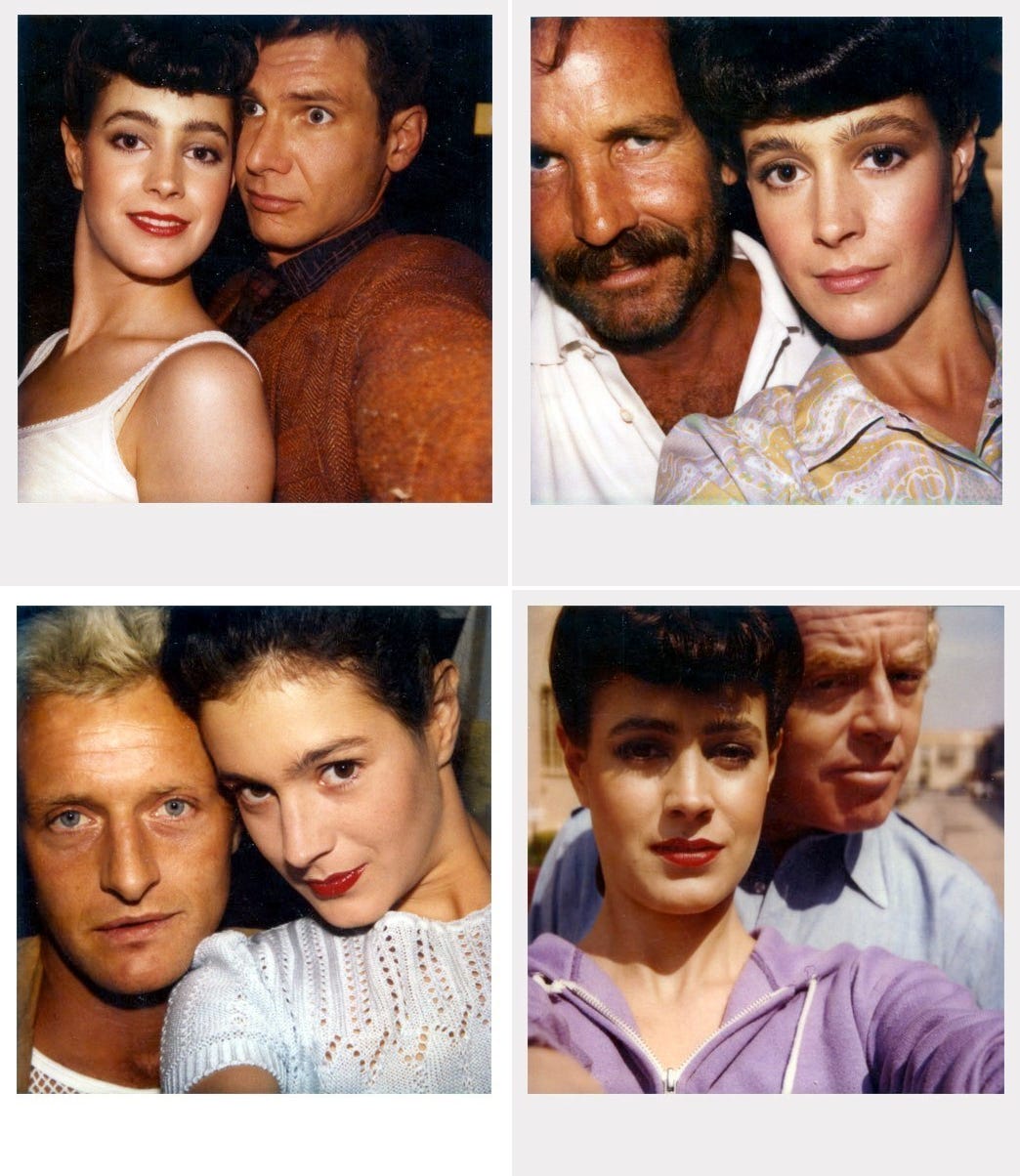

Sean Young took polaroids on the set of BLADE RUNNER.

The year was 1991. Actress Sean Young was trending — which in the Nineties means tabloids were dumping on her. The scandal: she barged onto the Warner Bros. lot dressed as Catwoman for an audition for Batman Returns. Two years earlier, Young was set to play Batman’s love interest in the first film, but she fell off a horse on set, fracturing her shoulder, so director Tim Burton replaced her with Kim Basinger. Young believed she deserved an audition for the sequel’s villain. After all, she was Sean Young. She played Chani in David Lynch’s original Dune (a role a not-yet-born Zendaya would reprise in a remake). She made love to future Yellowstone star Kevin Costner in No Way Out. Sure, Blade Runner flopped in its initial release, and the Wachowskis hadn’t yet cast Carrie-Anne Moss and a series of other black-haired Young lookalikes as heroines in sci-fi flicks like The Matrix, but by 1991, everyone knew Young’s role as cigarette-puffing, TERF-banged, maybe-robot Rachael was influencing a generation of blockbuster filmmakers. She was a star.

But Burton refused to see her, the media howled — and now, Hollywood was buzzing about that oh-so-difficult actress.

Publicists would tell Young to shut up (she is a woman in 1991, after all), but Young had a better solution. She went on The Joan Rivers Show and strutted across the stage in a Catwoman costume.

“How dare you not even return the Catwoman’s phone calls,” Young hissed at the camera. “Seems to me old Timmy takes himself pretty serious now, so I’m going to do you a favor and help you check into reality for a minute!”

The audience laughed. Young ripped off her cape, collapsed on a chair beside Rivers and sank back into reality. She giggled at her stunt. Decked out in a yellow pantsuit, Rivers cackled right back at her. They were two biddies poking fun at a scandal.

At least, they were for now. Halfway through the show, after a commercial break, Rivers welcomed Dr. Judy Kuriansky to the faux-living room set. The studio audience went silent. “She’s here to help us better understand much better what celebrities face when dealing with the anxiety and the stress and the agony of defeat,” Rivers explained. She turned to Dr. Kuriansky: “[Young] is putting herself on the line. Is it healthy?”

“Very!” Kuriansky said.

Young gasped, broke into tears and fell into Kuriansky’s lap. “I’ve wanted someone to say that for so long,” Young wailed. Sure, she mocked herself. Sure, she laughed. But she hurts beneath all the giggles. She’s relieved to hear someone call her normal. But, then, she paused. This couldn’t be true. She looked up, confused after too many years in La-La Land: “Why is it healthy?”

“Because [Sean] is not afraid about saying what you want and going for it,” Dr. Kuriansky said. “Sometimes you’re going to get in trouble for it.”

“Mostly, they say that I’m crazy!” Young said.

And boy did they. It’s hard to imagine now in the age of Free Britney and everyone from Paris Hilton to Pamela Anderson repositioning themselves as victims in memoirs, but Young’s career imploded. She was canceled before cancel culture existed, but many of her scandals were ahead of their time. In the Eighties, she tussled with actor James Woods before the media turned on him for his conspiracy theories. She rebuffed Harvey Weinstein’s advances years before Gwyneth. The first week of shooting Dick Tracy, she rejected Warren Beatty’s come-ons, so he allegedly fired her. (All the men deny the accusations, and Beatty has claimed he fired Young for not seeming “maternal.”) Instead of staying mum or waiting decades to recount her traumas in a Netflix documentary, Young often broadcasted the names of the men who did her wrong in real-time.